The hand is my feeler with which I reach through isolation and darkness and seize every pleasure, every activity that my fingers encounter. With the dropping of a little word from another’s hand into mine, a slight flutter of the fingers, began the intelligence, the joy, the fullness of my life.

–Helen Keller, “A Chat About the Hand” (1905)

We may never be able to think and feel as deeply with our hands as Keller did. Having lost the ability to both see and hear before the age of two, Keller had more reason than most of us to develop her extraordinary sensitivity. But we all undoubtedly think with our hands, even if this largely goes unrecognized or uncultivated. Researchers call this interaction between the body and mind—with the body sometimes leading the way—as embodied cognition, and their insights are changing the way we live, from our work to our play, and even the existence of a line between them.

It is common knowledge that children learn by manipulating things. We buy them the world in miniature (kitchen sets, dollhouses, cars and figurines) and they use it to imitate real life. Through play that is both fun and engaging, the uninhibited child learns to solve problems, and this has far-reaching consequences in the real world.

But this form of learning is not reserved for children alone. Born in 1878, Frances Glessner Lee, who was denied a college education, but who nevertheless went on to establish the first chair in forensic science at Harvard, miniaturized 18 rooms that were identical, down to the tiniest details, to actual crime scenes. These exquisite works of art were used to instruct and educate police detectives on how they should analyze evidence. Called the “Nutshell studies of unexplained death,” Lee’s method, as well as the original rooms that she built, continue to be used for training today. Her genius lay in harnessing the power of play.

A more familiar example of changing scale and working out problems with our hands is the game of chess. Originating in sixth-century India, this aristocratic game, which was known then as chaturanga (catur meaning “four” and anga meaning “limb”), used miniature representations of the four army divisions mentioned in the Mahabharata—infantry (pawn), cavalry (knight), charioteers (rook) and elephantry (bishop)—to engage in a battle of wits. This 64-squared board game later became known in Persian circles as shatranj, and even later as chess among Europeans.

The beauty of games is that they cultivate a sense of fun even as they require us to work out solutions to complex problems. Indeed, it is the very state of spontaneity and creativity afforded by games—or what Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi described in a different context as “flow”—that enables us to reorganize our knowledge, move beyond our own cognitive rigidity and, without necessarily intending it, come up with inventive solutions.

Creativity, however, can sometimes be disparaged. It can be seen as reflecting “a neglect of technical competence” or a “lack of methods or systems.” Similar things have been said of play. Yet creative thinkers, insist L.L. Thurstone and J.P. Guildford, the original purveyors of the idea of multiple intelligences, are among the best problem-solvers out there. Unlike obstinate bosses, orthodox companies, fundamentalist teachers, paleoconservative governments or biased news anchors, people who possess fluidity and flexibility in their thinking can easily redefine an object, situation or concept. Most importantly, they demonstrate a capacity to retain a sense of wonder in the face of a problem, or to accept the internal conflict that a problem creates.

For years I have worked hard to come up with creative solutions for my clients’ problems. Of late, however, I have begun to think that the best solutions are actually ones that my clients come up with themselves, as those are the ones they hold most dear. But how was I to facilitate originality and ingenuity, i.e. creativity, to help others help themselves get unstuck?

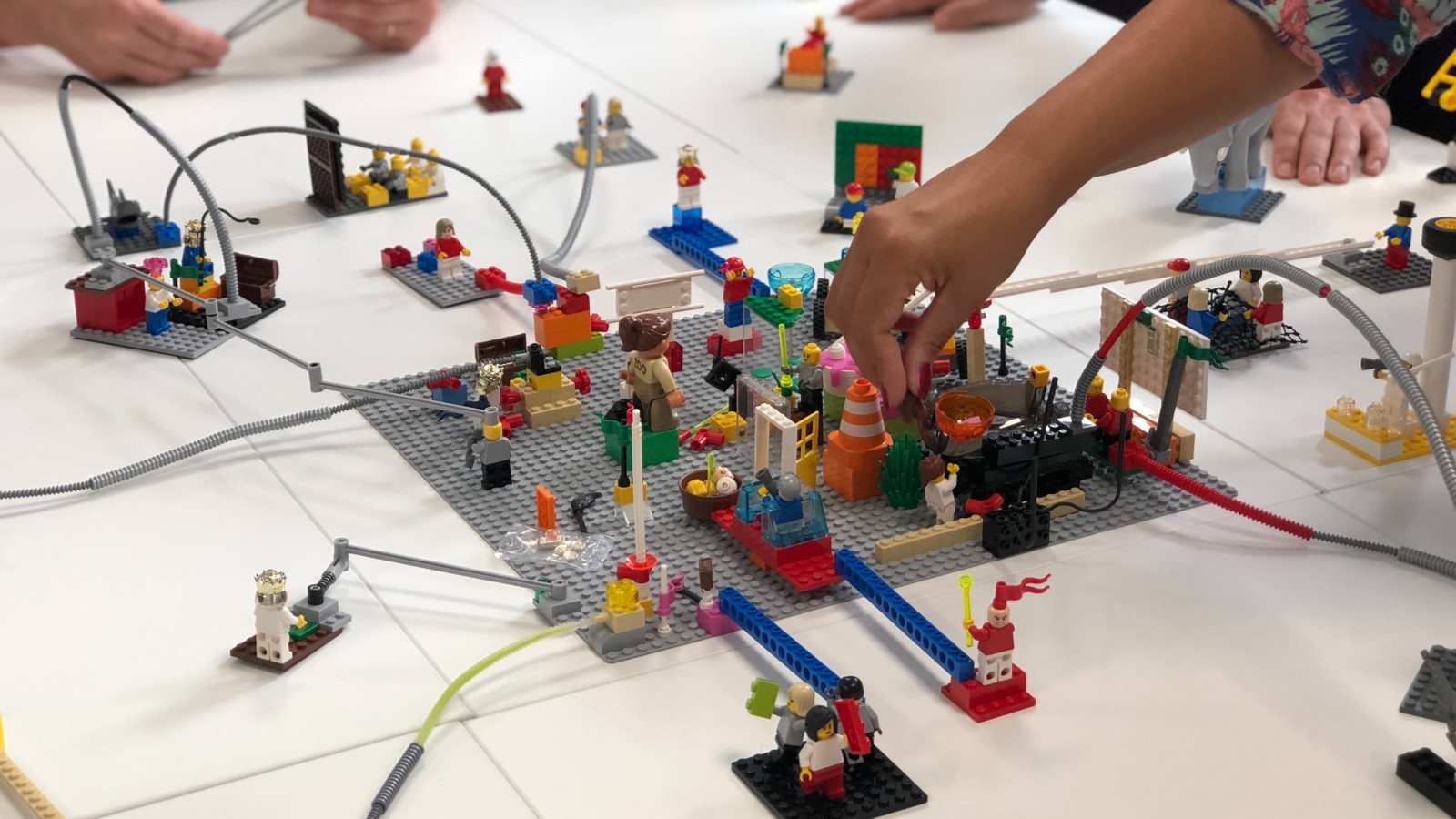

About a month ago I became an accredited facilitator of a relatively new methodology for learning and reflection called LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® which I will refer to as LSP (intellectual property is a touchy topic for them). Here is a method that checks all the boxes for me. First, it is haptic; participants see and feel with their hands. A key difference from normal LEGO® play, however, is that the objects being manipulated represent participants’ own mental representations in physical form i.e. they are metaphors. As a result, complex thoughts and emotions can easily be dissected, interconnected, reshuffled and altered. Second, LSP is, well, playful. This is something one might expect from the name LEGO®. But unlike games like chess, LSP has no fixed number of moves. Instead each brick is built to interlock with other bricks that are part of the “system,” making the number of combinations—and thus solutions—virtually unlimited. Third, all of this happens spontaneously thereby being physically and mentally present. This satisfies the conditions needed to induce a state of flow. In flow, inhibitions are averted and creativity awakened, often beyond what participants thought was capable.

As the roster of organizations utilizing LSP shows—from global corporations such as Coca-Cola, Google and Unilever, to governmental agencies such as NASA and the World Bank—creative solutions can, in fact, be cultivated. As Hungarian legend George Pólya rightly said, “ It is better to solve one problem five different ways, than to solve five problems one way.”

LSP offers elegant solutions to a messy problem.